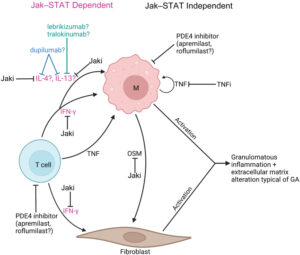

The pathogenesis of cutaneous granulomatous disorders is incompletely understood and many unmet needs remain in the treatment paradigm.1 These disorders can be categorized into two main groups: those caused by infections and those associated with inflammatory skin conditions, among the most prevalent inflammatory disorders are granuloma annulare (GA) and cutaneous sarcoidosis (CS).1 The presentation of both GA and CS is characterized by macrophage accumulation and inappropriate activation, resulting in an inflammatory response.1,2,3 The inflammation is then perpetuated by a macrophage–cytokine positive feedback loop (Figure 1).4 This inflammatory response has been highlighted in recent research as a potential new target for therapy, with a focus on blocking cytokine signalling via inhibition of the Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway with JAK inhibitors (JAKis).2,3 The approval of multiple JAKis in other dermatological indications provided further rationale, which led to observational studies investigating JAKi effectiveness in blocking this underlying pathway in cutaneous granulomatous disorders.2,3,5

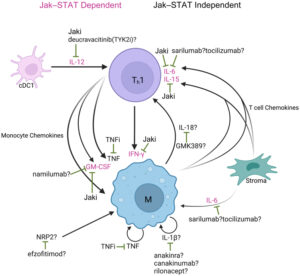

Figure 1: Molecular mechanisms of immunologically targeted therapies for GA and CS4

a) b)

a) Overview of proposed GA molecular pathogenesis and mechanisms of immunologically targeted therapy b) Overview of proposed cutaneous sarcoidosis molecular pathogenesis and mechanisms of immunologically targeted therapy. Reproduced from Hwang E et al, 2023, an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).4

cDC = conventional dendritic cell; GA = granuloma annulare; Jaki = Jak inhibitor; M = macrophage; OSM = oncostatin M; PDE4 = phosphodiesterase-4; STAT = signal transducer and activator of transcription; Th1 = T helper cell 1; TNFi = TNF inhibitor; TYK2i = tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor.

In this interview, Expert Faculty member Dr William Damsky starts by exploring the treatment landscape for GA and CS, established treatment options include corticosteroid creams, ointments or injections and other systemic medications. Although there are no United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapies for either cutaneous granulomatous disorder, other investigational therapies such as apremilast show some promise in GA.

Dr Damsky highlights his key research into cytokine signalling, which ultimately guided his study of JAKis as a therapeutic option for GA, and the clinical data from the small open-label trials he has conducted using JAKis in both GA and cutaneous sarcoidosis. Our interview then highlights the findings from his investigation of tofacitinib, a JAKi, in CS and the important part the study played in identifying a key cytokine that may drive the condition.

The interview then draws to a close with Dr Damsky underscoring the need for further data and randomized controlled trials investigating JAKis in granulomatous disorders and finishes with a discussion of the evolving treatment paradigm and what prospects may lie ahead for managing granulomatous disorders in the future.

Q. What does the current treatment landscape look like for granuloma annulare and cutaneous sarcoidosis?

There are no FDA-approved therapies for either disorder. While prednisone and corticotropin repository are approved for pulmonary sarcoidosis, when treating skin disease, we tend to try to avoid glucocorticoid-based regimens due to chronicity of disease and potential adverse effects.

So, presently all treatments for GA and cutaneous sarcoidosis are off label and unfortunately the evidence supporting any individual therapeutic intervention remains low due to the paucity of randomized controlled trials, especially in GA.

Q. Could you tell us about your research into cytokine signals in granuloma annulare, and how this led to investigating tofacitinib in this indication?2

We have performed molecular characterization of skin and blood from patients with GA which along with the work of others, is beginning to shed light on the key cytokine drivers of this disease. Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) appears to be elevated across cases and we believe a key therapeutic target in GA. Other cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-15, IL-21, oncostatin M, as well as IL-4 and IL-13 are likely to also play a role.

Tofacitinib is a JAK inhibitor. JAK proteins are required for transmission of signals from many cytokines (including all the cytokines above). Inhibition of JAK can reduce the heightened signalling of these overactive cytokines leading to clinical improvement.

Q. What data surrounds the use of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib in granuloma annulare and cutaneous sarcoidosis?2,3,5

The data remains limited in both diseases with evidence being derived from case reports, case series and small open-label trials. We would love to see these observations move forward into randomized placebo-controlled studies to better define clinical efficacy and safety of these medications in these diseases. Our ultimate goal is to generate evidence that could lead to FDA approval for medications in both of these disorders.

That said, although the experience with these medications is still limited to a relatively small number of patients, the efficacy that we have observed has been remarkable. Most of the patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis and GA participating in our trials have experienced life-changing improvement in their disease. Patients with uncontrolled disease for 10 years or more, often in the face of other commonly used treatments, have achieved clear skin for the first time with JAK inhibition.

Q. What did your study of tofacitinib in cutaneous sarcoidosis demonstrate in terms of interferon gamma inhibition?5

We performed an open-label trial of tofacitinib in patients with recalcitrant cutaneous sarcoidosis. In this study, 10 patients were treated prospectively with tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily for 6 months. We observed that all patients improved and 6/10 patients had complete clearance of their cutaneous sarcoidosis. Molecular studies were performed on skin tissue and blood as a function of treatment. We found that patients who had the best response had the most complete inhibition of IFN-γ. After the trial, we subsequently found that patients who had incomplete suppression of IFN-γ (and an incomplete clinical response) were able to clear their disease entirely with a higher dose of tofacitinib.

To us, this and other evidence suggest that IFN-γ is the key cytokine driving sarcoidosis. We believe that tumour necrosis factor (TNF) production (TNF inhibition being another commonly employed therapy in sarcoidosis) occurs downstream of activated IFN-γ signalling.

Q. What would be the next steps for developing JAKis in cutaneous granulomatous disorders and what does the future of the treatment paradigm look like?

We really need randomized controlled trials that ideally would incorporate translational immunologic approaches. Key questions are which JAK is the most important to inhibit (we think its JAK1 due to the role of JAK1 in mediating the signal from IFN-γ, while sidestepping haematologic side effects that might come along with inhibition of JAK2). Translational immunology will also help us to understand patients who do not respond, and the possibility of whether disease endotypes with varying immunology exist. Last, the role of topical JAK inhibition must be further investigated. We are working hard to make sure these things happen!